These days, every news channel you encounter is covering some aspect of the COVID-19 vaccine. One interesting but controversial topic is who should be given priority. On February 2, Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness and Canadian Network for the Health and Housing released a joint statement, advocating to prioritize COVID-19 immunization for people experiencing homelessness1. Should the homeless be given priority to the COVID-19 vaccine? For a plethora of reasons, the answer to this question should be an enthusiastic “yes”. The following will inform and inspire you to agree!

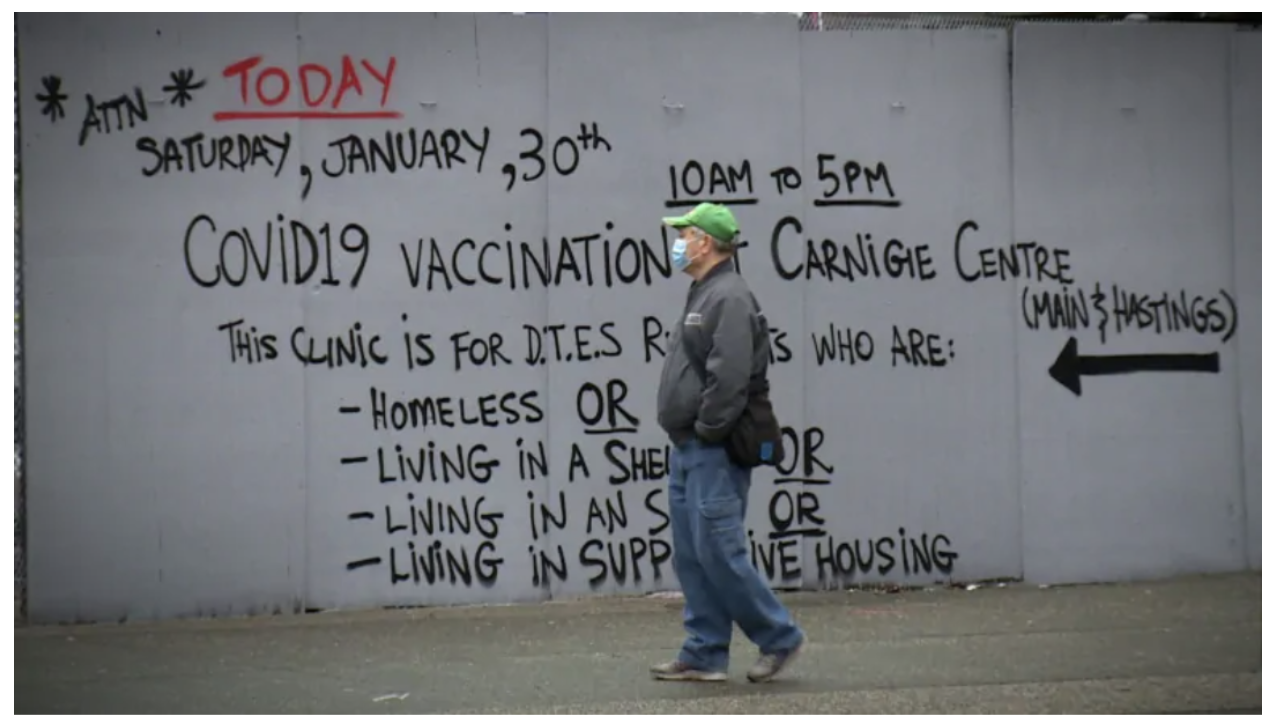

Vaccines have always worked; they currently work and will continue to work as science advances. To date, almost 250 million COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered worldwide. All Canadian provinces have started immunizing the priority populations. According to the Canadian government website, priority populations include adults of 70 years and above, health care workers and indigenous communities2. As important as it is to vaccinate these vulnerable demographics, the homeless population and shelter residents must also be included as a priority group. In fact, Montreal started the movement in mid-January to administer 500 doses to the homeless3. While the doses were limited, this initiated a movement across other provinces: Toronto, and later Vancouver, to consider and vaccinate their homeless citizens 4,5. But, how about the province of Alberta and more specifically, the City of Edmonton? Before getting to that, let us consider why supplying the homeless with the COVID-19 vaccine is crucial.

A key recent study in Toronto found that the homeless individuals, compared to the general population, were 20 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital due to COVID-19; more than 10 times more likely to require intensive care; and over 5 times more likely to die from COVID-196. It is shocking and deeply concerning to reflect on these staggering statistics. Perhaps even more surprisingly, it becomes apparent within the long-standing scientific literature that homelessness dramatically increases a person’s exposure to infectious diseases. For example, North American studies report the prevalence of hepatitis-B up to 13% in homeless youth compared to 0.8% in the general population7. Another example is HIV, where its prevalence is about 6% in homeless youth compared to 0.3% in young adults7. While the routes of transmission for these viruses are different, the rates of respiratory diseases that transmit similar to COVID-19 (e.g. influenza) are also higher in the homeless population8.

You may wonder why homeless people are at high risk of exposure to infectious diseases. This is a multifactorial problem that may be specific to each disease. Generally, one important reason is that homelessness is associated with a number of chronic diseases that are usually left untreated and increase the chance of getting an infection. For instance, many homeless people present with heart, lung or kidney disease, asthma and certain underlying immunologic diseases such as cancer8. These all increase the likelihood of hospitalization and death following an infectious disease. Another reason is that many shelters are overcrowded which makes it easier for the virus to jump from one person to another. So, if we knew all this, why did we not prioritize the homeless population’s access to get the COVID-19 vaccines?

Immunization for the homeless is difficult. One challenge is the lack of accessible health care resources. Even though most vaccines are free of cost in Canada, systematic barriers still exist. For example, those that live without a fixed address and proper identification documents have a hard time receiving care in some Canadian health care settings7. Other related issues include lack of consistency in vaccine eligibility knowledge and irregular vaccination policies among the homeless youth7. Poor access to health care ultimately translates into missed opportunities for vaccination, and it is also associated with distrust of the healthcare system and providers. Importantly, homeless people that have never encountered healthcare settings, or have never felt included in personal healthcare decisions are much less willing to receive care and trust physicians8. Another factor is that some homeless individuals may feel that healthcare providers lack compassion for the homeless. Finally, there is the issue of vaccination resistance. There are two types of vaccination resistances: intentional non-adherence, as in actively not accepting vaccination; and unintentional nonadherence, a passive process that leads to not getting vaccinated such as forgetfulness, scheduling conflicts or lack of knowledge about vaccine efficacy and safety9. Homeless individuals often exhibit the latter form of vaccination resistance as a result of the poor accessibility to receive vaccination information8,9. An accessible and effective education about vaccination safety and efficacy may help a great deal in addressing unintentional non-adherence in the homeless population. These challenges collectively make vaccination difficult and costly in this population. Considering all these difficulties, it is still possible to implement successful immunization programs when healthcare providers address these challenges in this vulnerable population.

There have been a few successful immunization programs in the homeless population. To give an example, in a large study conducted in Vancouver, 8723 individuals were immunized in an influenza/pneumococcal vaccination campaign and 3,542 were vaccinated for hepatitis-A and -B10. While it is not clear how many of these people were homeless, the targeted Vancouver area was estimated to have a large number of people living on the streets. Importantly, the vaccines were administered using outreach in a non-traditional setting, “vaccination blitz”. This meant that public health nurses and volunteers would visit different sites within the targeted area and vaccinate as many people as they could. This strategy turned out to be a great success as compared to traditional hospital vaccination programs: a lot of people participated. Preliminary results from the study showed that the rates of hepatitis-A infections and the number of hospital visits due to pneumonia decreased in the 3 months following the blitz10. Interestingly, COVID-19 vaccination blitz programs are currently underway in the United States (e.g. Chicago)11. Vaccination in non-traditional settings has proven to be effective mainly because it increases the accessibility of vaccines, decreases distrust of the healthcare setting and reduces vaccine resistance8,10. Canada and Edmonton could use such methods to deliver vaccines to the low-income neighbours within the homeless community. Prime Edmonton locations might be tent city or the neighborhood surrounding the coliseum.

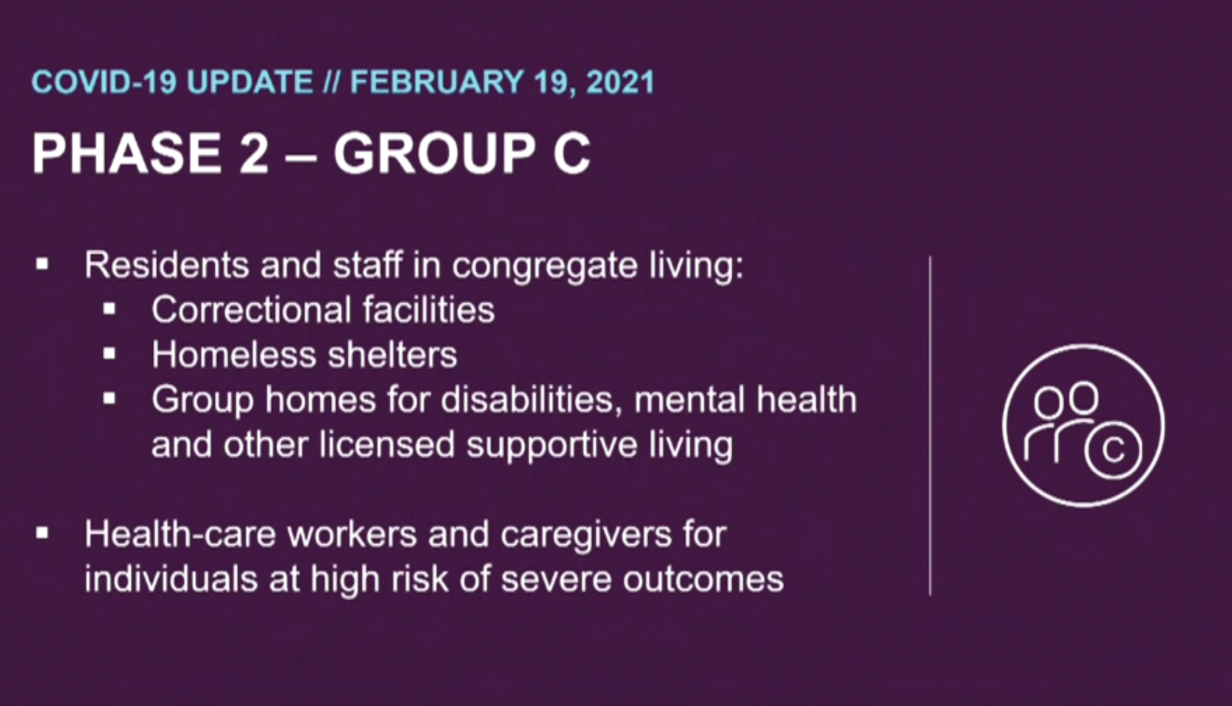

On February 19, the government of Alberta released a plan for phase 2 of COVID-19 vaccination which will take place from April to September12. The homeless and residents of shelters are in group C after group A (e.g. elderly and indigeous Albertans) and group B (those with underlying health conditions). While this step taken by the Alberta government is a good start, immunization of the homeless should have been initiated earlier similar to other Canadian provinces. In addition, no clear timeline has been given for when each group will be vaccinated, and group C will be vaccinated only after groups A and B are completed. Perhaps most surprising of all is that homeless individuals are not included in group B, while it is known that a large proportion have underlying health conditions that are untreated. It is also important to note that Alberta is currently facing a vaccine shortage, shipment issues and under-funding for healthcare. Nevertheless, the living conditions of people living on the streets is unacceptable and requires immediate attention. The homeless are readily exposed to the virus and in grave danger of suffering from its consequences. We must demand better health care for this highly vulnerable population.

While you may have little power to directly change the plans of our government, I know we can all play our part and do better to provide support and care for the homeless. Actions to achieve this can be as simple as educating yourself and the people around you by spreading awareness about increasing accessibility of vaccination for the homeless. I encourage you to have a look at the resources I have listed below to more deeply inform yourself on this important issue.

Additional Information:

Track COVID-19 Vaccines Worldwide: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

COVID-19 Vaccines in Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/covid19-industry/drugs-vaccines-treatments/vaccines.html

Alberta COVID-19 vaccination plan: https://www.alberta.ca/covid19-vaccine.aspx?utm_source=google&utm_medium=sem&utm_campaign=Covid19&utm_term=Vaccine&utm_content=v1&gclid=Cj0KCQiA-OeBBhDiARIsADyBcE7zobONx0ljacgmSnDrhP2zZGNtMg47N98G2CIq51yoh9Yd0qC-zmcaAraBEALw_wcB

CDC’s frequently asked questions – COVID-19 vaccination in the homeless population: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/homeless-shelters/vaccine-faqs.html

Key Advocacy/Research Groups to Follow and Support:

Canadian Network for the Health and Housing: http://cnh3.ca

Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness: https://caeh.ca

Dr. Stephen Hwang Research Team (world renowned Canadian scientist addressing homelessness and health) http://stmichaelshospitalresearch.ca/researchers/stephen-hwang

Science Up First (addressing misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines): https://www.scienceupfirst.com

Works Cited

- “STATEMENT: prioritize vaccinations for people experiencing homelessness, Canadian Network for the Health and Housing, 2 Feb. 2021, http://cnh3.ca/prioritize-vaccinations/

- “Vaccines and treatments for COVID-19: vaccine rollout”, Government of Canada, 25 Feb. 2021, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/prevention-risks/covid-19-vaccine-treatment/vaccine-rollout.html

- “Montreal to begin vaccinating homeless population after spike in COVID-19 cases”, Montreal, CBC News, 13 Jan. 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/montreal-homeless-vaccination-quebec-1.5871668

- “City of Toronto and partners start COVID-19 vaccination pilots for people experiencing homelessness and frontline workers in select shelters”, City of Toronto, 18 Jan. 2021, https://www.toronto.ca/news/city-of-toronto-and-partners-start-covid-19-vaccination-pilots-for-people-experiencing-homelessness-and-frontline-workers-in-select-shelters/

- “Vancouver health authority rolls out COVID-19 vaccine on downtown eastside”, CBC British Columbia, 30 Jan. 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/vancouver-health-authority-rolls-out-covid-19-vaccine-on-downtown-eastside-1.5895158

- Richard, Lucie, et al. “Testing, infection and complication rates of COVID-19 among people with a recent history of homelessness in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective cohort study”. CMAJ Open. vol 9, no 1, 2021, E1-E9

- Doroshenko, Alexander et al. “Challenges to immunization: the experiences of homeless youth.” BMC public health. vol 12, no 338, 2012

- Beers L, et al. “Increasing influenza vaccination acceptance in the homeless: A quality improvement project”. Nurse Pract. vol 44, no 11, 2019, 48-54

- Gadkari, Abhijit S, and Colleen A McHorney. “Unintentional non-adherence to chronic prescription medications: how unintentional is it really?.” BMC Health Services Research. vol 12, no 98. 2012

- Weatherill, Shelagh A., et al. “Immunization Programs in Non-Traditional Settings.” Canadian Journal of Public Health”, vol 95, no. 2, 2004, 133–137

- “Chicago Targets 15 Hard-Hit Communities For A Vaccination Blitz To Fight Disparities”, WBEZ Chicago, 17 Feb. 2021, https://www.wbez.org/stories/chicago-targets-15-hard-hit-communities-for-a-vaccination-blitz-to-fight-disparities/86b224d5-21dc-4914-936b-bd64d8c93855

- “Alberta premier announces priority list for second round of COVID-19 vaccinations”, The Star, 19 Feb. 2021, https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2021/02/19/residents-in-long-term-care-supportive-living-fully-vaccinated-alberta-premier.html

- “Alberta announces details about Phase 2 of COVID-19 vaccine rollout”. Global News. 19 Feb. 2021, https://globalnews.ca/video/7651379/alberta-announces-details-about-phase-2-of-covid-19-vaccine-rollout

Written by: Amir Ali Adel

Edited by: Jane Porter