As one of the most devastating global health crises in decades, the COVID-19 pandemic completely ravaged economic systems, societal structures, and thousands of livelihoods.[1] While the world appeared to be falling apart, many began to struggle with their mental health, as the isolation, instability, and chaos were starting to take their toll. Tragically, the pandemic exacerbated the challenges that individuals faced with their mental health by increasing the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts and behaviours.[2][3] Although the degree of these struggles varies from person to person, a few similarities have emerged.

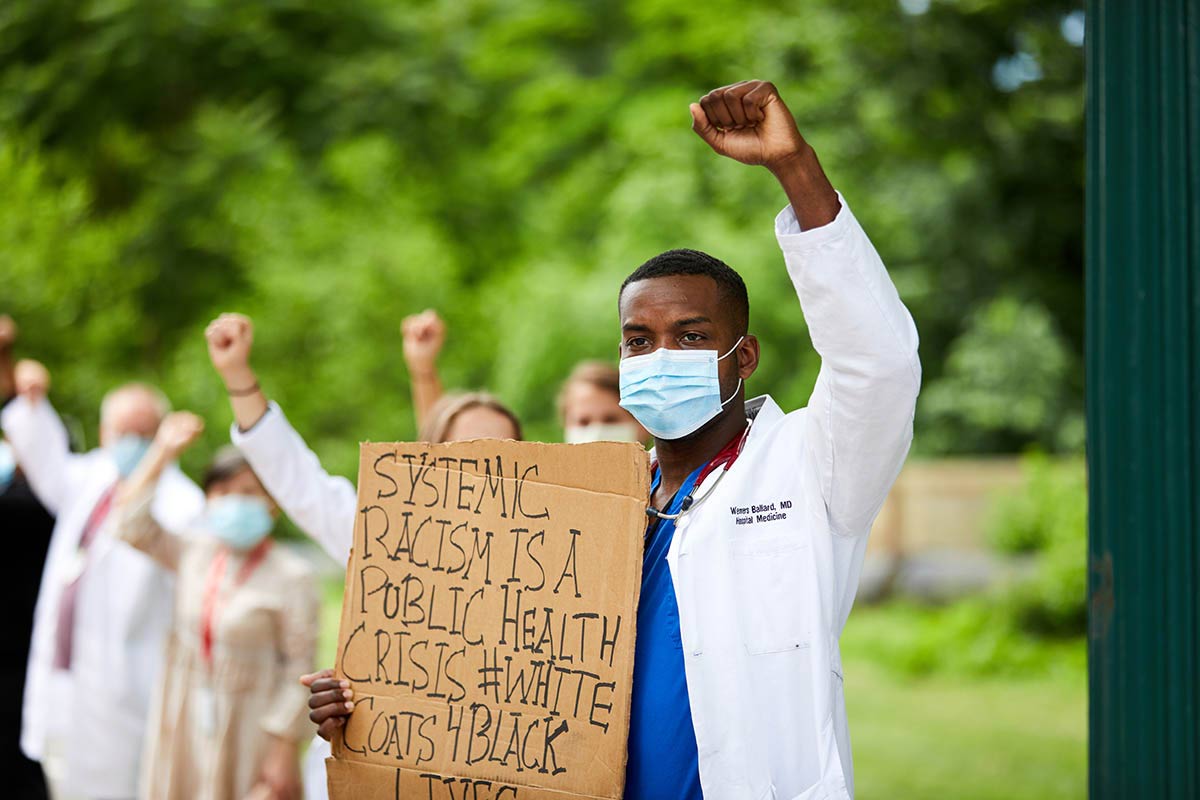

For instance, it has become evident that one of the most common symptoms that individuals are experiencing is elevated levels of stress. Especially in healthcare workers, the unprecedented changes in protocol and increased workloads have intensified exhaustion. Additional factors responsible for their debilitating fatigue include inadequate organizational support, overwhelming increases in people seeking care, and moral injury from witnessing thousands of patient deaths.[13] To put this into perspective, a staggering 60% of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists reported symptoms of burnout; consequently, these emotional burdens have triggered a troublesome increase in suicidal ideation within the healthcare field. [4][5][6] In addition to frontline workers, children, adolescents, and other civilians have also endured elevated mental strain, as food insecurity, school closures, and economic instability have created new challenges in their everyday lives.[8]

Moreover, another predominant pattern revealed by studies is the severe effects of the pandemic on the mental health of minority groups; this includes Indigenous peoples, people of colour, and those with disabilities. [7] A Canadian university student whose experiences exemplify these magnified struggles faced by minority groups is Zaid Baig.[14] During the pandemic, Baig began to severely struggle with his mental health, as he found it difficult to cope with the isolation, hopelessness, and shift to virtual learning. Eventually, Baig’s mental anguish became so unbearably intense that he attempted to physically harm himself. After reaching this breaking point, Baig realized he needed to seek psychiatric support; however, since Baig’s South Asian descent makes him part of the Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) community, cultural stigma became a barrier to receiving care. In minority communities like these, members struggle to find mental health professionals who can understand their cultural backgrounds and experiences. As an additional challenge, different cultural perceptions of mental health can prevent people from seeking help, as talking about mental struggles can be seen as a taboo. The challenges faced by these vulnerable populations were amplified, as they had less access to resources, proper health care, and mental health support.[9]

While it may seem like the pandemic is behind us, the effect that it has had on our mental health continues to linger. To make matters worse, poor insurance coverage for mental health services and long wait times have imposed treatment barriers for many. Even in the time following the pandemic, no significant changes have been made to insurance policies. While private insurance providers do provide some mental health coverage, typically between $500 – $1500 annually, this only accounts for the cost of approximately 2-8 counseling sessions; often, this isn’t enough to fully help those in need.[15] Therefore, the only option for those who require more sessions or don’t have insurance altogether is to pay out-of-pocket. Considering that mental health care continues to be rather unaffordable, this creates unnecessary financial burdens on many individuals. Additionally, the prolonged wait times for therapy sessions, psychiatric appointments, and inpatient treatment programs are also preventing people from receiving help. To illustrate the intensity of this problem, some Canadians have been on waitlists for up to 2 and a half years, due to the surge of those seeking care.[15] For instance, since the demand for eating disorder treatment programs soared following the pandemic, wait times have also increased. Consequently, because of this lack of availability, doctors are needing to wait before admitting patients who are already in life-threatening conditions. This is especially evident in Sally Chaster’s experience. Chaster, a Canadian woman struggling with anorexia nervosa, needed to wait a staggering eight months before accessing treatment services.[16] Bearing in mind that anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of all mental illnesses, this could have become a catastrophic situation, as Chaster was unable to receive help when she first needed it. Ultimately, these long wait times are detrimental for all who are suffering mentally, as they allow an individual’s symptoms to prolong and intensify; concurrently, this negatively interferes with their quality of life, as these barriers prevent them from receiving the help they desperately need.

During the peak of the pandemic, various efforts were made to help the influx of those requiring support; however, we cannot stop now, as this continues to be an ongoing crisis. Although this has been a harsh wake-up call, we can use this as an opportunity to strengthen the mental health response across the world. By raising awareness, we can begin to advocate for increased funding, more resources, and better support. The road ahead may seem daunting, but it doesn’t diminish the value of the destination; with proper action, change will be possible. Undoubtedly, community-based initiatives and mental health service providers are excellent resources for support, but listed below are 6 tools that you can use to foster a better sense of well-being! Additionally, there are some tips on how you can help loved ones with their mental health, while also working towards achieving SDG 3!

Give Yourself Permission to Relax

Relaxation is crucial in managing stress, as it can regulate your heart rate, improve brain functioning, and help you switch off your fight or flight response. Although it can be difficult to intentionally allow yourself to take breaks, starting small will be beneficial in allowing you to feel less overwhelmed, anxious, and stressed. Relaxation practices can vary from person to person, but some common techniques include breathing exercises, meditation, or simply being mindful while completing an activity you enjoy.

Prioritize Proper Sleep

While it may be tempting to stay up late, lack of sleep has proven to increase feelings of despair, hopelessness, and distress. Therefore, good-quality sleep is essential for your well-being, as being well-rested improves your mood by reducing irritability, enhancing concentration, and energizing you to engage in positive behaviors.

Take Care of Your Physical Health

Without a doubt, our physical health and mental health are intertwined. Even small amounts of exercise can benefit your mental health, as regular physical activity releases endorphins that enhance your overall well-being. If you feel comfortable, you can go to the gym, or you can do something as simple as going for a walk or riding your bike. Additionally, ensuring that you’re staying hydrated and eating a healthy, balanced diet is crucial, as it improves your brain functioning and allows you to feel your best. Minimizing caffeine intake can also help alleviate some symptoms of anxiety, especially feelings of restlessness.

Talk to Someone You Trust

It can feel overwhelming when hundreds of thoughts seem to be spiraling in your head. Talking about your struggles to a friend, family member, teacher, or another trusted individual can provide you with a sense of relief. It can allow you to feel less alone, acquire a new perspective on your situation, and free yourself from the thoughts and feelings you’ve trapped inside.

Practice Gratitude

When we’re struggling with challenges, it’s easy to forget about the good that remains in our life. Even though you may not always feel grateful about anything, starting to appreciate the little things that you take for granted can improve your mood, restore hope, and promote happiness. Practicing gratitude can be as grand as writing out a list every day, or as simple as thinking about something you appreciate.

Reach Out For Help if You Need it

Asking for professional help is never a sign of weakness but of strength. If you ever feel like you need additional support or are unable to cope with the symptoms you’re experiencing, you don’t need to struggle in silence. Regardless of your situation, you are valid and there are many supports available to help you. Doctors, therapists, and social workers are some of the professionals you can reach out to, and listed below are some resources you can use.

- Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868

- Talk Suicide Canada: 1-833-456-4566

- 911: If you or a friend/family member expresses an intent to harm themselves or others and are in immediate danger, call emergency services.

- First Nations, Metis, and Inuit Peoples Hope for Wellness Crisis Line: 1-855-242-3310

https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1576089519527/1576089566478

- 24/7 Mental Health Helpline For Albertans: 1-877-303-2642

How To Support Loved Ones Who Are Struggling

If you have a friend, family, or loved one who is struggling with their mental health, it can be difficult to know how to effectively support them. Although they might be withdrawing themselves from you, make an attempt to talk to them. When doing so, don’t force them to open up, but present them with an opportunity to talk. For instance, you could ease into the conversation by mentioning that you’ve recently noticed that they’ve been struggling and that you’re willing to listen if they want to talk. If they do choose to open up, be respectful, empathetic, and attentive to what they’re saying. Instead of invalidating their feelings, offer reassurance by understanding their perspective; genuinely acknowledge that this is a difficult situation for them. Even though you may not be a mental health professional, you can suggest resources, recommend coping strategies that help you, and offer to help in whatever way you can! As always, if this individual is in immediate danger to themselves or others, call 911.

Written by: Tiara Gonsalkoralage

Edited by: Zuairia Shahrin

Works Cited

- World Health Organization. (2022, June 16). The Impact of Covid-19 on Mental Health Cannot Be Made Light Of. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-mental-health-cannot-be-made-light-of

- United Nations. (n.d.). Goal 3 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations. Retrieved February 21, 2023, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3

- World Health Organization. (2022, March 2). Mental health and covid-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/352189

- World Health Organization. (2022, March 2). Covid-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

- Stress in Healthcare Workers: A Model to Help us Rethink Challenges. McGill University Health Centre. (2022, May 3). Retrieved February 28, 2023, from https://muhc.ca/news-and-patient-stories/news/stress-healthcare-workers-model-help-us-rethink-challenges

- Koontalay, A., Suksatan, W., Prabsangob, K., & Sadang, J. M. (2021, October 27). Healthcare Workers’ Burdens During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8558429/

- Covid-19 and Suicide – Mental Health Commission of Canada. (n.d.). Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/covid_and_suicide_tip_sheet_eng.pdf

- Tracking the COVID-19 economy’s effects on food, housing, and employment hardships. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2022, February 10). Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-economys-effects-on-food-housing-and

- COVID-19: The Disproportionate Impact on Marginalized Populations. COVID-19: The Disproportionate Impact on Marginalized Populations | Jane Addams College of Social Work | University of Illinois Chicago. (2020, April 29). Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://socialwork.uic.edu/news-stories/covid-19-disproportionate-impact-marginalized-populations/

- Mental health and Covid-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact. (2022, March 2). Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/352189/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci-Brief-Mental-health-2022.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- World Health Organization. (2022, October 13). Impact of Covid-19 on People’s Livelihoods, their Health and our Food Systems. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news/item/13-10-2020-impact-of-covid-19-on-people%27s-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems

- World Health Organization. (2021, October 7). 6 ways to Take Care of your Mental Health and Well-Being this World Mental Health Day. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from https://www.who.int/westernpacific/about/how-we-work/pacific-support/news/detail/07-10-2021-6-ways-to-take-care-of-your-mental-health-and-well-being-this-world-mental-health-day

- Murthy, V. H. (2022, July 13). Confronting Health Worker Burnout and Well-Being | Nejm. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2207252

- Anand, A. (2023, February 1). Taboos and therapists who don’t understand: Mental health struggles more complicated for BIPOC Youth | CBC News. CBCnews. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/mental-health-bipoc-youth-struggles-stories-ottawa-1.6730187

- Moroz, N., Moroz, I., & Slovinec D’Angelo, M. (2020, July 2). Mental Health Services in Canada: Barriers and cost … – sage journals. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0840470420933911

- Dubois, S. (2022, August 13). Wait times for eating disorder treatment in Canada grow during the pandemic | CBC news. CBCnews. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/wait-times-for-eating-disorder-treatment-in-canada-grow-during-the-pandemic-1.6533635