All Canadians have the right to access healthcare. Discriminatory treatments, however, make it difficult for minority groups such as Black, Indigenous, and people of colour to exercise this right. A historical case that exemplifies healthcare’s mistreatment of Black people is an American physician, Samuel Adolphus Cartwright’s invention of the ‘mental illness’ drapetomania in the 1850s. What this ‘mental illness’ entailed is as ridiculous as its name makes it sound: the disease that made the slaves desire freedom and run away. Cartwright also created another illness named dysaesthesia ethiopica which purportedly made the slaves indifferent to the punishment given by their owners. These made-up diseases were used to justify how Black people were psychologically and physiologically suited for slavery. Another historical case is the one that occurred in the 1940s, when Indigenous children were forced to starve in six residential schools. The Canadian physicians took advantage of such conditions in order to study the effects of malnutrition. They experimented on the children by altering their diet which consisted of meals that were minimal in quantity and abhorrent in quality. Russell Moses, an Indian Affairs Branch employee who attended the Mohawk Institute in Ontario, from 1942 to 1947, explained that “hunger was never absent” for him and other children in residential schools.

How does our healthcare system treat minorities today? Perhaps racism is not as overt as it was in the past. Or so we might think. But it surely exists in our current healthcare system. The mistreatment of an Indigenous man from Manitoba, Brian Sinclair, sheds light on undeniable racism in healthcare. In 2008, Brain was referred to the emergency department of Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre by his primary care physician and was met with 34 hours of negligence. He eventually died due to complications of a bladder infection that was treatable had he been taken care of by the physicians immediately. Furthermore, a request to inquire into Brian’s death was denied by the Manitoba government. Only after five years passed since his death did the inquest begin. The inquest revealed how discriminatory actions from health care professionals led to the tragic and unjust event of his death. There were multiple witnesses who testified that staff made assumptions about Brian such as that he was intoxicated or homeless. Nurses, despite their claim that they have never noticed Brian, were seen in the hospital’s camera to have walked right by him when he was in urgent need of help. In January 2014, however, it was ruled that racism was beyond the mandate of the inquest which meant that the role of racism, on both an individual and systemic level, will not be analyzed when it comes to patient health.

Presence of racism can not only be seen in single instances but also in statistical data of collected experiences of minorities in healthcare. In a study done by Husbands et al., among 1360 Black Canadian participants living in Toronto and Ottawa, around 60% reported experiencing racism within 12 months before the study. The likelihood increased if participants were older, employed, born in Canada, obtained high levels of education, identified as LGBTQ, and reported to have moderate access to basic needs and housing. Apart from age and LGBTQ identity, many of these factors are generally thought of as positive social determinants of health. This suggests that these social protective factors still are not sufficient in preventing Black Canadians from experiencing racism. Further, it was reported that one of every five participants felt difficulty accessing healthcare, and of those, 25% attributed such difficulty directly to racism, while 30% and 10% attributed it to more specific reasons that are indirectly related to racism. Moreover, Black Canadians were less likely to be tested for HIV due to their experiences with racism. Such effects of racism contribute significantly to health inequities between Black Canadians and other demographics.

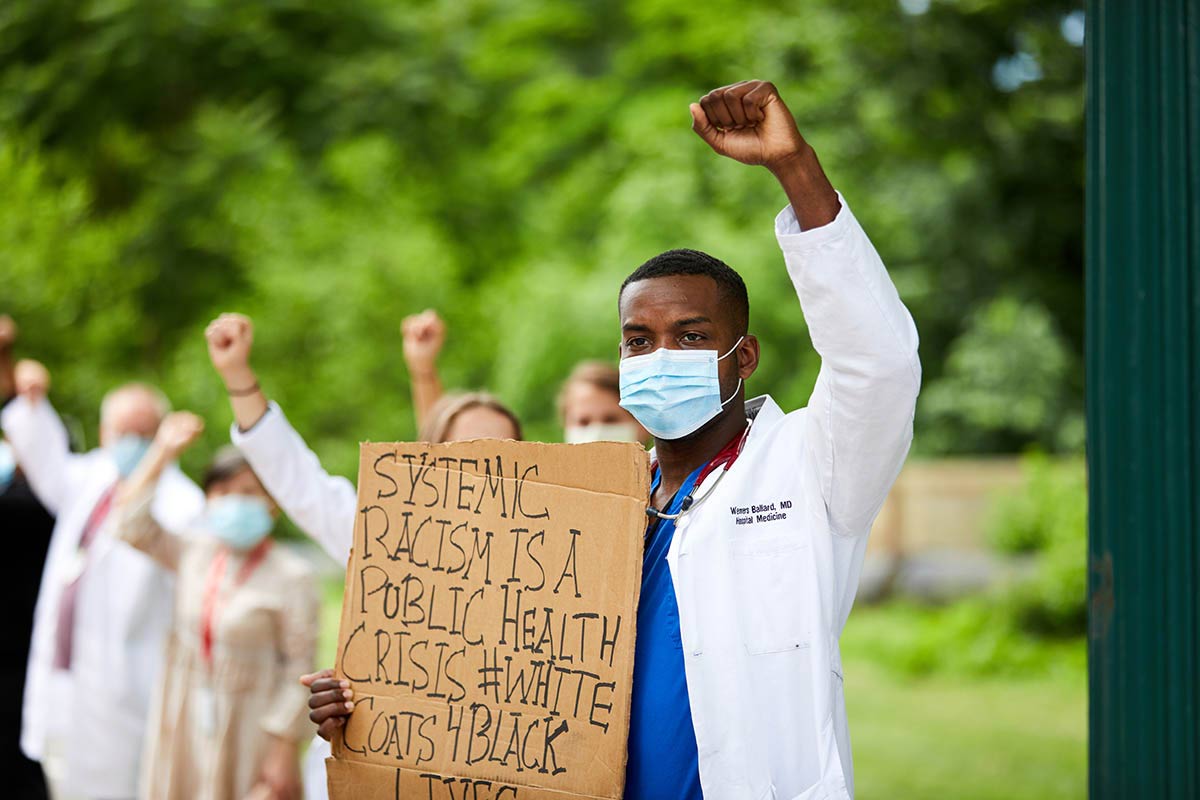

From historical cases to modern ones, in both case studies and population-scale research, it is evident that the Canadian healthcare system often mistreats the minorities in our society. It is clear that racism is a prominent and an important issue in healthcare that ought to be resolved. As citizens of a country that embraces multicultural values and harmony, we must take whatever steps we can to help fight against racism in our society as well as advocate for minorities’ voices to be heard.

Written by: Erica Kim

Edited by: Zuairia Shahrin & Kritika Taparia

Works Cited:

“Drapetomania: When Fighting Oppression Is a ‘Mental Illness.’” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/machiavellians-gulling-the-rubes/202105/drapetomania-when-fighting-oppression-is-mental-illness.

Husbands, Winston, et al. “Black Canadians’ Exposure to Everyday Racism: Implications for Health System Access and Health Promotion among Urban Black Communities.” Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Oct. 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9447939/.

Mosby, Ian, and Tracey Galloway. “‘Hunger Was Never Absent’: How Residential School Diets Shaped Current Patterns of Diabetes among Indigenous Peoples in Canada.” CMAJ, CMAJ, 14 Aug. 2017, https://www.cmaj.ca/content/189/32/E1043.

Nourish. “Ignored to Death: Systemic Racism in the Canadian Healthcare System.” Nourish Leadership, Nourish Leadership, 29 Apr. 2021, https://www.nourishleadership.ca/resources-1/2021/4/9/ignored-to-death-systemic-racism-in-the-canadian-healthcare-system.