Introduction:

Homelessness impacts people of all identities, but none so much as people of Indigenous identities. Indigenous peoples are inordinately affected by homelessness, and this is only amplified when considering rates of youth homelessness. It is estimated that between twenty-five and thirty-five thousand Canadian homeless youth identify as Indigenous (2). When considering disproportionate representation in youth homelessness, it is critical to understand North American and Canadian-specific forms of colonialism that have direct relationships to youth’s experiences today (1). Legacies of North American colonialism such as parental neglect, physical and sexual violence, and family or personal poor mental health are only some of the challenges faced by Indigenous youth that contribute to homelessness (2). In conversation with an elder in the Metis community, it is evident that these risks to Indigenous youth are long-endured and unchanging. Supports to those at risk of homelessness (or even the homeless themselves) are not highly accessible, and psychological legacies of colonialism are often found to be at the root of Indigenous youth homelessness. Although social programs are created to aid and support homeless youth, it can be a further challenge to promote access to these resources, especially due to the historical treatment of indigenous youth in residential schools.

Colonization of Indigenous Peoples:

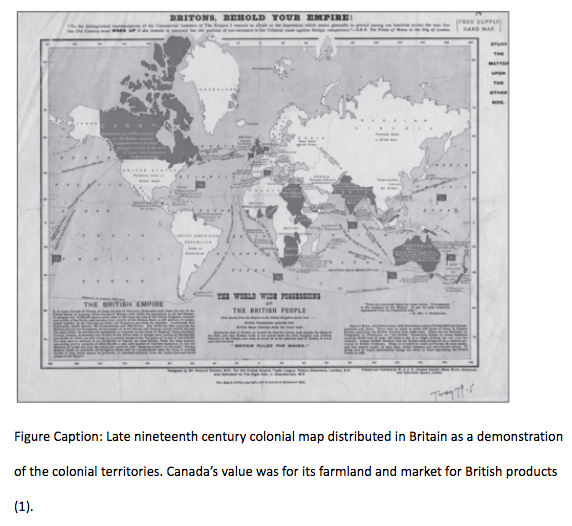

Historical context is key to understand the disproportionalities in homelessness when discussing homelessness as an Indigenous issue. European colonialists settled the land that is now known as Canada, beginning the interaction between themselves and the Indigenous people who occupied this land for millennia (1). Colonialism is the practice of overtaking a region outside of a colonialist’s own country and economically exploiting the land or people of that region. Although interactions such as the fur trade benefited both ethic groups, actions of colonialism by the British Empire (and later by Canadians) caused enduring negative legacies for indigenous peoples (1).

European perspectives on the Indigenous way of life can be summarized as considering Indigenous peoples as “savage” and “uncivilized”. These perspectives drove missionary interaction and mistreatment of Indigenous peoples, leading to large-scale operations and legislative actions that have supported negative legacies of Indigenous treatment in Canada. The most notable examples are residential schools and the Indian Act (1). Residential schools were created in their first form pre-confederation, and involved horrific mistreatment of Indigenous youth, who were stripped of their cultural identity and their community and family through “education”. The Indian Act was a post-confederation piece of legislation that required assimilation of Indigenous peoples and denied Indian status to many Indigenous men and women. The act also removed Indigenous autonomy to self-govern, giving the Canadian government veto power over any band’s decision (1).

Residential schooling of Indigenous youth continued until 1996 in Canada, and left devastating repercussions that will remain for generations (1). Assimilation was a pillar of these institutions and abuse within them was frequent. The Indian Act was amended in 1920 to require all Indigenous children to attend residential school. The peak of residential school attendance was during the 1960’s during an era of gross forceful removal of children from their homes called the “Sixties Scoop”. Life at Residential school was often faced with hunger, unsanitary living conditions, and emotional or physical abuse by those responsible for the youth’s well-being (1). Legacies of these horrific conditions in residential schools, that we now characterize as cultural genocide, can be directly related to the significant rate of homelessness effecting today’s Indigenous youth.

Interview:

A recent study found that homeless Indigenous youth cited reasons of physical or sexual abuse, and personal or parental drug and alcohol abuse or mental health issues as reasons for leaving home. 54.4% of homeless Indigenous youth experienced pre-street physical abuse, and 23.3% of homeless Indigenous youth experienced pre-street sexual violence (2). In an interview with an Edmonton local Métis residential school survivor who experienced homelessness for a majority of her life, she cited her reason for leaving home to be parental violence against herself and her siblings. Growing up in an environment with a father struggling from severe alcoholism, she suffered through physical and psychological abuse and ultimately felt that the only option for her survival was to leave home. Though she is uncertain about her father’s experiences with residential school, she found it highly likely that he experienced negative treatment in a residential school. After leaving home, however, her challenges only grew during her time on the street. Post-street exposure to drugs and alcohol as coping mechanisms is common for Indigenous youth: 45.1% of homeless Indigenous youth are hospitalized due to a drug or alcohol overdose (2). She explains that her experience frequently involved drug addiction and routine hospitalization as a result. Often, she elaborated, youth on the street are taken advantage of by older homeless people in order to secure drugs and alcohol, or to exchange drugs and alcohol among one another. It should be stated that alcoholism and drug addiction are considered diseases and are not based solely on the individual’s choices. For more details please read the previous blog post “The Russian Doll of Stigmatization”.

Programming and Aid: New Solutions

When asked “what do you think would be the most helpful resource for Indigenous youth who have left home?”, the local elder responded that she believes it is the accessibility of information on where to get aid from social programs that is the largest challenge. Once homeless youth know where to access aid, the last hurdle facing Indigenous youth is trusting that source of aid. Non-indigenous removal of indigenous children from their homes is deeply intertwined with the legacy of residential schooling, leading to a lack of trust between indigenous children and programs like child-protective services (2). While it has always been an immense challenge for homeless Indigenous youth to trust shelter or child-protective services for aid, she believes that this it is more possible now than ever before for Indigenous youth to trust those resources due to the Truth and Reconciliation governmental campaign that is advocating for better supports for today’s Indigenous peoples who are still impacted by the devastating legacies of colonialism (1).

Resources and supports for homeless populations are not always readily accessible to those who may need them. When addressing her transition off of the street, the interviewee indicated that during her experience she was unaware of services such as Hope Mission, the Mustard Seed, or local women’s shelters until she was much older. If she had had access to those supports earlier on in her life after leaving home, she believes that her life may have taken a turn for the better. Although she was unsure about what the best way to inform homeless youth about support systems would be, her recommendations included putting up signage around homeless communities, and to teach young school children what to do when they are in a crisis situation.

A national study on homeless Indigenous youth recommends that indigenous-led preventative and interventional programs for domestic issues should be formed as a method of reducing Indigenous homelessness (2). This study found that many of the homeless Indigenous youths who have interacted with child-protective services have had negative experiences with these kinds of organizations. These negative experiences include but are not limited to abusive foster homes, culturally unaware foster homes, or removal from an otherwise supportive community (2). By developing an Indigenous-led, culturally aware network of support for Indigenous youth in conjugation with psychological aid for traumas faced as a result of the legacies of colonialism, it may be possible to reduce Indigenous youth homelessness.

References:

1. Anonymous What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation [Online]. http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Principles_English_Web.pdf [Nov 21, 2020].

2. Kidd SA, Thistle J, Beaulieu T, O’Grady B and Gaetz S. A national study of Indigenous youth homelessness in Canada. Public Health 176: 163-171, 2019.

Written by: Jane Porter

Edited by: Kritika Taparia and Anson Wong